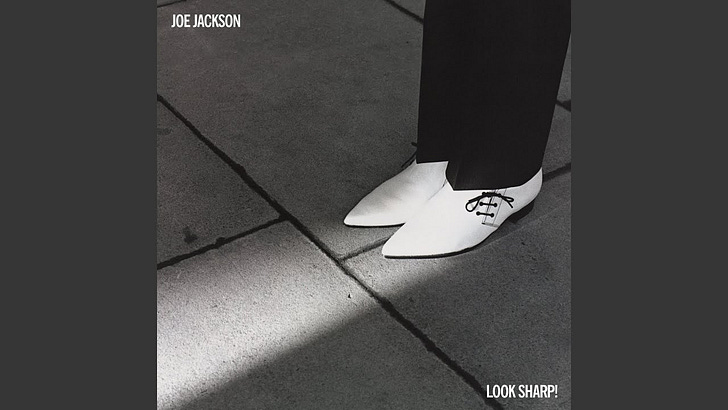

The opening lyrics of the Joe Jackson song:

Fools in love

Well are there any other kind of lovers

Fools in love

Is there any other kind of pain

Everything you do

Everywhere you go now

Everything you touch

Everything you feel

Everything you see

Everything you know now

Everything you do

You do it for your lady love

And then, later:

Fools in love

They think they're heroes

'Cause they get to feel more pain

I say fools in love are zeros

I should know

I should know because this fool's in love again

The lyrics are good, but to do the song justice, you need to hear the words sung with the plaintive, but sharp edge of Jackson’s voice. I’ve pasted a YouTube of the song at the bottom of this post.

Jackson is singing about His Lady Love, a singular type of all-consuming romantic love. I can relate to that type of love and, when I was under its “everything” influence, can relate to having acted like a fool. (See Love, Fool below.)

But first. As I’ve grown older, I’ve accrued many other types of loves. All of them come with their pleasures, but none without some measure of pain.

There’s love for your children (and grandchildren), love for your children’s spouses and their families, love for your siblings, love for your parents, love for friends, too. More people to love each year. And for me hardly any attrition. My mother died in early 2020, and I love her today as much as I did when she was alive. I don’t worry about her, but I miss her. My best memories of her are bittersweet, the bitter part being the realization that memories of her are now finite. That memory factory has been permanently closed.

If you love someone, you generally look forward to being with them both for the time together and to make more memories. You derive sincere happiness from their triumphs and good fortune. But when they suffer, you suffer too. For family, this empathy comes naturally. For friendship, a measure of love may be how deeply you feel a friend’s joy at a triumph or sadness at their suffering. Schadenfreude and envy are inconsistent with love for a friend. To my pleasant surprise, I’ve found myself adding new and true friendships over these past few years.

One of my most consequential new loves is for our dog Sophie who we’ve now had for almost five years. She’s my first pet, and she has given me tremendous and wholly unexpected joy. The fact that she will not be around forever is something I dread. I think about it rarely, but when I do I am filled with a sadness that is hard to express, almost as if without her, my life will become empty, stale, and flat. I worry about the shock that would come with Sophie’s death, although I hope it’s a decade or more away.

So with love comes worry. I tend to be analytical to a fault, and so when someone I love is under duress or threat, my mind turns automatically first and foremost to thinking about what I can do to help. As well, I think about what I should avoid doing to worsen the situation. Many times, in fact most times, there is little I can do so I am left simply with the worry and the empathetic feelings.

Being overly analytical about those I love leads me to consider not only their current situation but also thinking about what might happen a few steps ahead. If you have the instinct and the ambition to help, you think about “what-ifs” and project the problems of your loved ones into the future.

So, to use a consultant’s matrix of Strengths, Opportunities, Weaknesses, and Threats, love is the ultimate Strength (Hallmark, take note!), but each object of love also carries with it a degree of Weakness/Threat, i.e., the vulnerability of sadness, loss, and worry. There is a natural limit, I believe, to how many people we can legitimately love. I’m sure that this capacity varies both by person and by age.

An extreme and supernatural illustration of empathy run amok is portrayed in Stephen King’s “The Green Mile,” one of his finer books and among the best of his movie adaptations. The character, John Coffey, is on death row in the 1930s South for murders he did not commit––– he’s a gigantic black man found holding two young white girls. Coffey is overwhelmed by a supernatural ability to feel the pain of others and has the ability through touch to cure their pain at tremendous physical cost to himself. That’s what he was trying to do with the murdered girls when he was apprehended. His antennae for picking up suffering grows so extreme that Coffey’s in constant agony, and he welcomes the release of the electric chair.

So like almost anything else, empathy must be moderated.

Love, Fool

When I first met my wife in October 1984, I followed the blueprint of at least part of Joe Jackson’s song. Everything was about Debbie to the exclusion of virtually anything else that was possible to set aside. I had a rival for Debbie’s love, and that did cause me pain and, because I was in love, I was super determined to win.

One foolish consequence of my “Lady Love” obsession was to ignore completely my long time, best friend Steve with whom I was set to share an apartment that following January. Instead of being his partner in our “wild and crazy” bachelor pad fantasy, I disappeared into my romance with Debbie, and as a consequence Steve was understandably hurt and became extremely jealous.

My friendship with Steve went south, something he was much more aware of than was I. Finally, at the rehearsal dinner the night before our wedding, Steve went around the room telling people, including my younger brothers, that I was making a mistake and that our marriage would not last long. When I heard this, my reaction, unprompted by Debbie, was to disinvite him to the wedding. That was the end of the friendship.

Handled by me throughout like a true fool in love.

However, being a fool in love was an exquisite and consequential way to exist with an exceptional clarity of purpose. And, yeah, Joe Jackson, I did think I was a hero!

Wonderful piece!

A wonderful description of love and friendship that I shall remember. Thank you.