Hello Failure My Old Friend

My personal struggle to feel like a success in collaboration with writer Laura Kennedy. My essay first, then a link to hers, and then a short video conversation between Laura and me.

Success looks different depending on where you start. In this collaboration, I’m exchanging essays with

who grew up in Ireland in a working class home with no serious advantage beyond an exceptional single mother who encouraged her to write. I’m a sixty-two year old guy from Manhattan born into generational wealth and the expectations that went with it.Despite our differences there’s a similarity to the questions Laura and I are trying to answer about advantages, disadvantages, social mobility, and how money influences our notions of success. My essay is below and a link to Laura’s essay follows.

Money

From an early age and up until recently my idea of success was based on money and the power that came with it. “We begin by coveting what we see every day,” says Hannibal Lector in The Silence of the Lambs. What I coveted is what my older sister had.

Her bedroom and mine were at the end of the children’s hall, but hers was vast, twice the size of mine. Our respective wealth was denominated in comic books, and her Archie collection was not only far larger but kept in pristine stacks while mine were torn, food-stained, scattered, and justifiably often thrown into the garbage by the housekeeper.

I wanted to read my sister’s comics, while she had no interest in mine––mostly war, horror, and superheroes. So she exercised power over me by forbidding me from borrowing her comics.

My sister’s power was enhanced further by her willingness to confront my mother who wielded a vicious temper and was the de facto god of our household while my sister and I were mortals and my father somewhere in between. I saw power in my sister’s bravery, perhaps the more so because her rebellions against my mother ended with my sister in tears.

Seeing the pain my sister suffered, I became the “good boy.” I was frightened of being yelled at or punished. I shrank from confrontation. I was motivated to do well in school.

As we grew a little older, I did find a way to exercise power over my sister. She loved to gamble, and she and I would gamble at backgammon for hours at a time.

I won money from her consistently. I tracked my winnings with great care. As her debt to me grew, we played for larger and larger sums. It was understood that my sister had no means of paying me while she was still under eighteen. When the debt grew to five figures, I made her sign handwritten promissory notes secured by her inheritance. No one had told me that we would inherit money. I just assumed, correctly, that we would.

Occasionally, my sister would ask me for a few dollars, and I’d add these negligible sums to her debt. I’d delight myself with the power I had as her legal creditor. And that when we did inherit, I’d start off with more money. I don’t remember the peak of her indebtedness but it was probably the equivalent in the 1970s to one hundred thousand comic books.

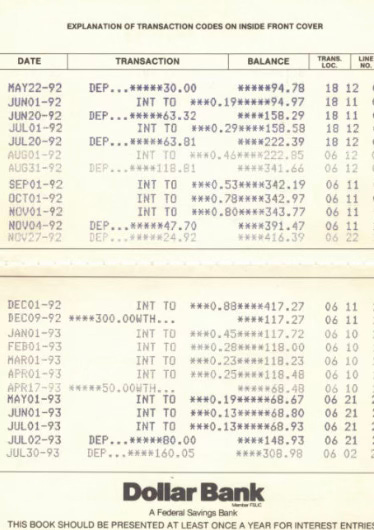

The money she owed me was as real to me as the amounts recorded in my Lincoln Savings Bankbook. It was my first taste of wealth and power.

Until one day I demanded that my sister make a good faith payment. Whereupon she appealed to my father who’d had no idea of our shenanigans. Without consideration of due process, he immediately cancelled all debts and outlawed gambling. My sister was jubilant; I was crushed.

A simplistic definition of success

What’s given to us doesn’t feel like success.

I grew up in a wealthy family and I had an expectation that I’d never have to struggle for money. But I knew that whatever money was given to me would not be enough for me to feel successful. I set the bar of money success by my grandfather. He’d made a fortune as an oilman in the 1930s, sold out at the right time, and then came East to invest in the stock market.

He had a house on the Jersey Shore built of stone, which defined for me what a mansion was. As well, it was his money that enabled my mother to buy the 7,000 sq. ft. apartment we lived in on Park Avenue. I grew up wanting to live in a house like his and an apartment like ours.

I saw that my grandfather’s wealth gave him confidence, respect, and influence. The ideas I had of success in my youth were simplistic and perhaps quintessentially American. Money plus power. They were also hard-wired. As if my brain cells and synapses had hardened over my juvenile ideas, preserving them like amber preserves a fossil.

How we create our own success trap

Why are we so often perverse in choosing how we measure success? We disregard what comes easiest and focus on what’s most difficult.

My father warned me early on that I’d never get credit for my financial success because I was born into a wealthy family. That just made me more ambitious.

After college I went to work on Wall Street convinced that my skills as a student, my facility with numbers, and the energy of my ambitions would launch me on a path of extreme success. But as I advanced, I found that my gifts had limitations. I lacked boldness and I assumed that those who behaved and carried themselves with confidence were better than I was. That they knew secrets I didn’t know. They intimidated me, and my shyness made me a poor networker.

As I became older, the mark of “real” success, the peers I compared myself to, were those who founded their own firms and flourished. I considered myself a mediocrity because given my head start and my intellectual capabilities, I thought I should have been at the very top. It was my own very bespoke version of Instagram envy.

I’ve written a lot about my marriage and my children and my happy family life. But until recently that part of my life didn’t register with me as “success.” It came easily and naturally to me so I didn’t feel like I’d had to struggle for it. The fact that I wanted to spend as much time as possible at home, the definition of a “homebody,” seemed to be a success flaw not a virtue. I thought I should have been going to business dinners and traveling for business to advance my career.

It wasn’t until I was fifty that I could see how my family life formed a large part of my self-esteem and thus should be incorporated in my definition of success. At my 50th birthday party all my children gave toasts that focused on the time I’d spent with them while they were growing up. I look back at their toasts as a long overdue wake-up call.

Diversification of my success definition

A few years ago I left Wall Street to find other vocations. I found writing, a vocation almost guaranteed to have nothing to do with increasing wealth. I’ve come to love it.

I possess no writing advantage. I start with blank pages and blank screens just like every other writer.

Attempting to quantify my success as a writer is an elusive, foolish, and arguably destructive pursuit. For now, it feels like success that some people spend time reading these weekly essays.

However, when the words aren’t flowing, I’ll wonder what the hell am I doing. Where’s the reward, what’s the point, who cares?

Then someone will tell me that one of my posts meant something to them, and I’ll feel like a writer.

I’ve come to realize that a satisfying definition of success needs to have a degree of difficulty to it but it also needs to fit, realistically, within the circumstances of your life––your background, your personality, and your stage of life.

I also now believe that pinning your definition of success on one single aspect of your life is reckless and a path to almost guaranteed unhappiness.

Still, I have a habit of looking at someone else’s life and assuming they possess the self-confidence of success that eluded me for so long. It’s what I previously assumed about my writer friend Laura Kennedy, so self-aware and such a phenomenal and deservedly popular writer at such a young age.

Read what Laura has to say in this link to her essay on success

And check out her newsletter

. I’ve been reading and enjoying her incisive personal essays about modern culture and her life since 2023.Laura and I recorded this short video to discuss our two posts.

Question for the comments: Do you feel like a success and, if so, when did that feeling begin?

When I teach about the 2008 Financial Crisis, my students generally wonder why the people running the banks, who were already wealthy enough to buy anything they could ever want, kept manipulating the economy to enrich themselves further until the whole thing crashed. I tell them that beyond a certain point it ceases to be about having money and become about having MORE money, which is a psychic need unconnected to actually material reality. For my part, I think you should be prouder of your work here than on Wall Street. After all, here you started at the same level as everyone else and earned every reader through hard work. That’s success by any measure.

Laura and David, I am going to write one comment for both of you now that I have read both and watched the video. (I can't comment on Laura's article so will just write to both of you here.) First, thanks for this wonderful collaboration. I have been reading both of you for some time and enjoy the insights you provide. Second, this idea of success is one that has been rattling around in my mind lately, particularly how subjective it is.

Growing up poor I had this idea that success meant monetary wealth or at the very least, having "things." Nice house, nice clothes, nice job, nice wife, nice kids, etc... Quite naive in retrospect but for a young boy in rural America who was raised to believe in the pursuit of the American Dream, these seemed perfectly normal at that time.

In my career in the Navy over the course of 24 years I thought success meant getting good performance appraisals, getting promoted ahead of my peers, getting selected for premier positions of authority, etc...

It was quite the wakeup call to discover that my kids knew next to nothing about my work and would rather I have spent more time at home than off sailing the seas. Even though my version of success provided nicely for our family, that wasn't particularly relevant to my wife and children who would have preferred me to be with them.

One of the reasons I have not gone back to work since retiring from the Navy last year is the desire to force myself to slow down, an attempt to be present for my wife and children in a way I wasn't previously. I realized that it wouldn't matter so much how much money I made or what nice things we have if I didn't have a relationship with those I loved.

Even recently I have struggled to reign myself in here on Substack as it is so easy to compare ourselves to others. I started seeing some growth in subscribers (which is wonderful of course) and is certainly a measure of success in writing. However, at the same time I noticed less personal engagement and a sense I had to "perform" to a certain level to keep the growth going. Suddenly I was distracted again by my perfectionist, workaholic mindset, seeking a false idea of success.

These past few weeks I needed to sit myself down and give myself a stern talking to. So I appreciate the insights that you both provide here. There are many different ways to measure success but some are certainly going to have a much longer lasting impact than others.

Keep up the great writing, both of you. All the best, Matthew