A Look At Privileged Healthcare Within A Barbaric, Unjust, And Stupid System

How self-interest perpetuates the status quo

While I was working on this post, the CEO of United Healthcare was gunned down in Manhattan, probably by someone who was personally and grievously affected by United’s denial of insurance coverage.

Any sympathy for the victim and his family was subsumed beneath an outpouring of rage against United Healthcare, rage against for-profit insurance companies, and rage against the American healthcare system. The anger was so intense that on-line expressions of glee at a man’s murder were prevalent. 1

I promised at the end of last week’s post to describe with transparency what it’s like to have privileged healthcare in contrast to what most Americans experience. While I don’t seek to enflame the discourse, I intend to keep my promise.

When you have privileged healthcare, it’s easy to look away from the significant flaws in our healthcare system that most Americans have to endure.

Further, if you fear that a fundamental change to the system might jeopardize the quality of your own care (or raise your taxes or harm the value of your investments in the for-profit healthcare system) your self-interest can lead you to oppose change even if it means opposing what is just and moral.

There is a clear overlap between those who enjoy privileged healthcare and those who influence and decide the limits of debating what a different and more just healthcare system might be.

That’s why I think it’s important to tell the personal story below.

Ruling out the worst

Exactly three years ago, on the memorable date of December 7th, 2021, I was with my wife Debbie in the airport headed to Palm Beach when her left pinky suddenly went numb. When we arrived at the hotel, her right foot suddenly became numb. Along with the numbness came pain.

Numbness on both sides is scary. A brain disease could be the cause. We needed to investigate immediately for our peace of mind.

We were staying at the grand hotel, The Breakers––the setting for a light-hearted post earlier this year about a decades old fight: A Fight Reveals The Fault Lines In Our Marriage.

When an emergency arises, staying at a hotel like The Breakers has its advantages. The hotel had an excellent concierge doctor on speed dial. We got an immediate appointment. The doctor gave Debbie pain relief treatment and arranged for a series of MRIs to test for the scariest causes. We paid out of-pocket for the visits and the tests.

We waited for the results with tremendous anxiety and were relieved when the tests ruled out the most serious diseases. Yet Debbie was in great discomfort and pain. She said, with some serious intent, that she wanted her pinkie amputated.

When we returned to New York, I contacted the Dean of the Medical School at the hospital we use to find out who Debbie should see. The Dean set us up with the hospital’s most senior neurologist, “Dr. Elio,” a diagnostic genius we were told. He saw us before he went on vacation to Hawaii and performed intense (and painful) tests to assess the condition of Debbie’s nerves.

Dr. Elio was flummoxed by his initial test results but was determined to nail down a diagnosis.

Great access but no cure

We have relatively robust insurance (available to me as a retired partner of my firm) that costs us about $30,000 a year in premiums. But the doctors we use generally charge us out-of-pocket and then we get some percentage of the cost back.

These are the doctors with the best reputations who can have thriving private pay practices because there are a lot of people in Manhattan who can afford to pay out-of-pocket. An annual check-up costs us about fifteen hundred dollars, is unhurried, and lasts as long as necessary, usually about an hour. Debbie’s neurologist visits cost about three thousand dollars.

The best doctors tend to have great sway in a number of ways. Within hours, they can sometimes get their patients in to see a specialist (often these doctors are in the same building or across the street––location is important). To the benefit of his patients, the “inside baseball” on Dr. Elio was that he was known as the “terror” of the radiology department. Saying no to him for a patient appointment was not an option. That’s part of what you’re paying for.

In the summer of 2022, Debbie called me in tears. The rest of her left hand had suddenly gone numb. She was frightened that she was going to eventually be incapacitated. That she wouldn’t be able to help our daughter care for our first grandchild due to be born later that year.

By the spring of 2023, Debbie’s symptoms had not abated. Since her initial Dr. Elio visit, Debbie had undergone numerous diagnostic nerve tests, various pharmaceutical interventions, a dozen MRIs, and an arm surgery. Dr. Elio was now more than flummoxed, he was beaten.

He told Debbie, “There is nothing more I can do.”

Naomi and the marathon visit

Debbie and I wanted a second opinion. She received a strong recommendation from a trusted doctor to see a different neurologist named Naomi. Debbie decided to present her case as a blank slate so that Naomi would not be influenced by the prior test results. A brilliant strategy.

In that first visit, Naomi spent four hours testing and talking with Debbie. Combined with a blood test identifying a rare marker, Naomi’s tests confirmed a diagnosis of a very rare autoimmune disease called MADSAM, which involves a thinning of the sheaths around the nerves.

The standard treatment for MADSAM is to undergo infusions of immunoglobulin. The private pay cost is something like $10,000 per infusion. Naomi told us we’d get insurance approval but that we would first have to do a dance with our insurance company even though her diagnosis of Debbie was “textbook.”

The insurance company dance went exactly as Naomi predicted. An insurance denial followed by persistent insistence from the insurance “tyrant” in Naomi’s office followed by a consultation between Naomi and the insurance doctor followed by approval. Expertise in getting insurance approvals is another skill you pay up for.

The good news is that after a year of treatments Debbie’s symptoms have improved. The initial delivery mechanism caused Debbie to have bad allergic reactions, so Naomi switched the delivery from intravenous to self-administered injections (sub-cutaneous), a relatively new way of delivering the immunoglobulin that Naomi was aware of.

We now feel we are on a good path to controlling and reversing Debbie’s autoimmune disease.

Wealth does not prevent the pain and frustration of getting sick, especially when you don’t know the cause. Nor does it alleviate you of the necessity to make your own good healthcare decisions. In hindsight, we should have left Dr. Elio earlier.

But wealth and health access can significantly improve your chances of a better outcome. It certainly did for us.

A few observations about American healthcare

1) We are the only wealthy country that does not provide healthcare as a right to all its citizens.

2) We spend about 50% more per capita on healthcare than our peer countries and have worse health outcomes, including a far lower life expectancy. The chart below is from a recent, comprehensive Commonwealth Fund comparison of the healthcare systems of ten wealthy countries. America ranks last in access, administrative efficiency, health equity, and health outcomes.

3) As one example, American maternal mortality rates are absolutely and relatively dreadful and ethnically unequal. For instance, our maternal mortality rate is four times worse than the UK and for black Americans nearly ten times worse. 2

4) The richest one per cent of American men have a life expectancy fifteen years greater than the poorest one per cent. The same statistic is ten years for women. Source: NIH report conducted by Raj Chetty. 3

5) Although most people in the United States are insured, their insurance generally comes with costly premiums, significant deductibles, co-pays, complexity, and periodic difficulty getting insurance approval.

After the murder this week, it was widely reported that United Healthcare is the leader in insurance coverage denial at almost one out of every three requests.

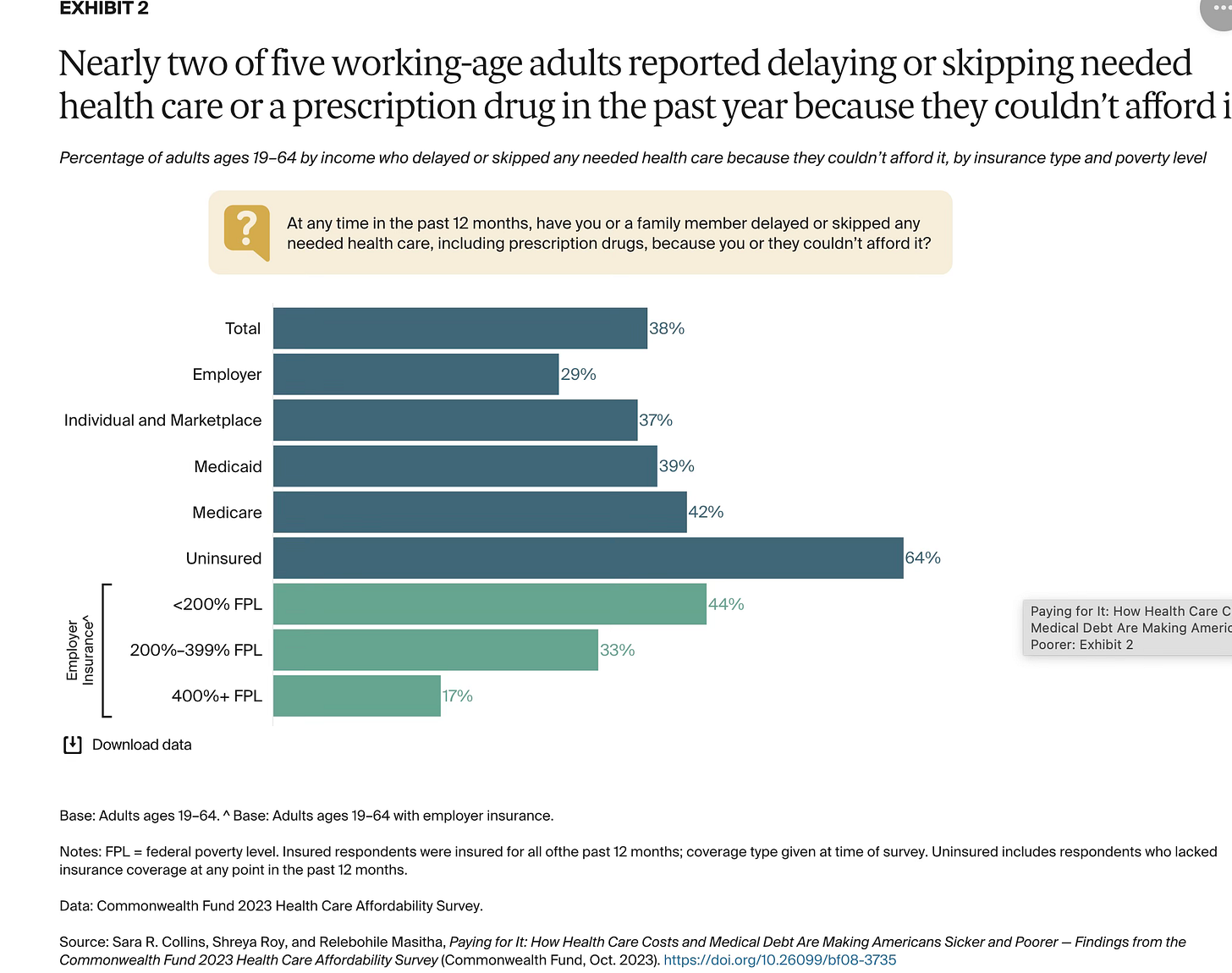

About 40% of working age Americans reported skipping or delaying needed healthcare in the last year because they couldn’t afford it. 4

Only in the United States would we expect to read an article called “GoFundMe Has Become A Healthcare Utility.”

Kirsten Powers and her viral post

When I first read

’ viral post The Way We Live In The United States Is Not Normal, I was annoyed. Obviously I was jealous that another Substack essayist had nailed what so many were thinking. Plus Kirsten came up with the perfect headline to describe why she had decided to move to Italy.More germane, her essay threatened my long held belief that while America might have problems, we still had a superior way of organizing our economy. And personally, I wondered if the American way of life I enjoyed was part of the problem Kirsten was outlining.

I owe Kirsten a debt of gratitude because she really opened my eyes about American healthcare compared to other wealthy countries. She continues to do so as she writes about her move to Italy. In her latest post she reported that she was able to get excellent healthcare insurance in Puglia, Italy for an annual premium of $1,000.

Part of the problem

The truth is that I have indeed been part of the problem, not so much in the healthcare I receive, but in my attitude. When I heard “Medicare for All” or “Socialized Medicine” or “National Health Insurance,” my knee jerk, irrational reaction was to think that my privileged healthcare would be taken away.

I now think my reaction was misguided and unworthy. But if that same reaction is held by most of the rich and powerful, then that’s one important reason the status quo persists.

I don’t pretend to know the right solution. But I recognize that our healthcare system is a problem that we as a country should fix.

And I know at some point in the future, the way we handle healthcare in America today will be seen as barbaric, unjust, and stupid.

I couldn’t find comparable country data for the richest and poorest 1%. This UK report, however, looks at the disparity in life expectancies within countries between that country’s bottom and top 10% geographic areas, a proxy for relative socioeconomic status. Using that method, the United States has a life expectancy disparity significantly higher than the UK, Italy, the Netherlands, and France.

The chart below is from the Commonwealth Fund 2023 Affordability Survey.

David, my husband, a retired physician who practiced for 30+ years in DC, responded to the murder with some version of “I don’t condone murder, but this guy allowed the blatantly unethical behavior of United Health to continue… “ In other words, doctors as well as patients are horribly frustrated by the insurance companies denying claims, charging fees that are too high, etc.

Thank you for writing this. We need change—it is unworkable for most Americans. My brother is a surgeon, and many of the cases he sees are low-income working people who could not afford primary or preventative care and then need to have limbs amputated. My mother was an ER doctor for 35 years, and felt horrible at the fact that she often needed to prescribe patients care or medicine without knowing whether they could afford it.

I’m an American living in Italy, and have been very satisfied at the care I’ve received in the public system; even when you seek care in private hospitals, the prices are posted clearly at reception. I find it totally insane that Americans must get treatment and often do not know how much they will pay beforehand.