I'm A Conservative But Not The Kind You're Thinking Of

By conservative I mean a preference for change that is gradual rather than radical. I also mean a love of tradition.

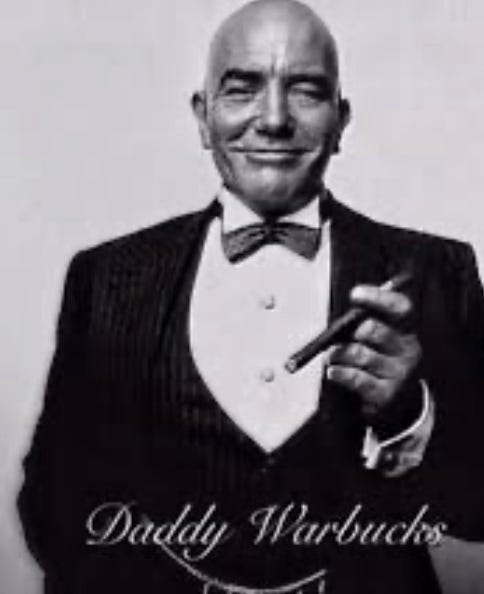

Your audio narrator Lauren Breskin noted the resemblance to Jeff Bezos

When we think of “conservative,” we may call to mind a wealthy Republican like Daddy Warbucks or an exclusive country club or The Handmaid’s Tale. Or small government and lobbying by the wealthy for lower taxes on the basis of “trickle-down economics.” I used to think I knew what “conservative” meant as a political label but I don’t anymore.

I’ve written often about being born into generational wealth, and it’s true that being wealthy has predisposed me, for most of my life, to fear big government, high taxes, and, at worst, the expropriation of property in violation of the rule of law. But I have different views now. 1

When I think of myself now as conservative, I think of my love

of nuance,

of reform vs. revolution,

of preservation through stewardship,

of a great wariness of nihilism––burn it all down–––because I know that many of us in our weary frustration, including me, can be prone to that dangerous line of thought,

and of tradition and precedent

Mr. Nuance

I don’t know what to label a politics centered around disliking sudden change. It’s neither right nor left. Sudden swerves in any direction disturb me. These swerves usually come about because others see a singular solution, one brightly lit, obvious path, whereas I generally see multiple factors and multiple paths.

If I were a veteran politician, god forbid, I might be known as Mr. Nuance, which would mean no one would vote for me. The name would be better used for a character in a cartoon for gifted children. Perhaps played in the costume of an octopus who can physically display multiple “on the other hands.”

Reform not revolution

My intellectual inspiration for “reform not revolution” is Edmund Burke, the 18th Century British politician and political thinker. Burke was for tradition and against sudden change. Yet Burke was in many ways an iconoclast. He was one of the earliest prominent British statesmen to speak out against slavery. 2

Burke was a vocal and prescient opponent of taxing the American colonies in the 1770s in contravention of a long policy of salutary neglect. He knew what would happen if there was a sudden change.

“Leave the Americans as they anciently stood…Do not burthen them with taxes…. [if British] sovereignty and their freedom cannot be reconciled, which will they take? They will cast your sovereignty in your face.”

Burke was best known for his condemnation of the violent 1789 French Revolution, which he compared unfavorably to the peaceful 1688 Glorious Revolution in Britan.

“The [Glorious] Revolution was made to preserve our antient indisputable laws and liberties, and that antient constitution of government which is our only security for law and liberty...The very idea of the fabrication of a new government, is enough to fill us with disgust and horror.”

Burke felt it was essential for Britain to remain connected to its past. To never break a chain forged over many centuries. He loved that bond with the past and his entire career was spent trying to strengthen it through reform.

Let us now praise stewards

Essentially, Burke saw himself as a steward of the English political tradition. Stewardship is a term we don’t use often enough in the sense of preserving important traditions and great institutions. In everyday usage, we might think of a steward as someone working on an airplane. Or Denethor from Lord Of The Rings, Steward of Gondor and worst steward ever. 3

It’s understandable that people might not get fired up at the prospect of being a bridge between what came before and what came after. This role of caretaking flies in the face of our yearning to be of memorable consequence as distinct individuals.

Yet institutions and families need stewards as much, if not more, than they need heroes and adventurers. In stewardship, you find satisfaction in being part of something with a long past and a hoped for long future. It could be a family and its values, a non profit institution like a great research hospital, a religious tradition, or a system of government. Even if your role is small and unheralded, there is still glory to be gleaned.

Apocalypse then

In opposition to stewardship is nihilism. The idea that the past and its principles have led us to an awful and meaningless place so we might as well destroy it all.

One of my favorite books from my college days was Stephen King’s The Stand (1978), one of the first apocalyptic, “technology will kill almost all of us” novels. There are many reasons why I loved that book but I think I especially loved it at nineteen because it fed my nihilistic fantasies. The idea that something huge and destructive would happen and the world would be remade in an epic battle of good vs. evil. 4

That impulse toward destruction may be at the heart of the appeal of all dystopian fiction, an impatience at the creeping, slow pace in reforming current problems compared to a global disaster that would replace old problems with new, more interesting ones.

I can’t tell how much of our current political climate is motivated by these nihilistic impulses, strange fires of the soul that in some people smolder for their whole lives and are never extinguished. I suspect certain fringe groups have those tendencies, and if their members ever read The Stand, they’d be rooting for the “Walking Dude.”

The rainbow sea

For the first time in my adult life I feel as if I’m facing a real nihilist threat, a sudden radical change where the rules and the norms of behavior I’ve come to depend upon seem to be at sea. And I’m easily made seasick.

Our family fatefully ate Fruit Loops before an Atlantic Ocean fishing excursion.

I don’t doubt there’s a sincere belief among many people that radical change is necessary and that it must happen right away, traditions and rules be damned. One of the commenters to my last post about the new administration wrote,

“sometimes you do need to throw the baby out with the bathwater.”

Another wrote,

“You can't fix all that damage, all the attacks on merit that unleashed gross incompetence with mealy mouthed compromise measures that don't handle… everything wrong when the Democrats decided to give away America to the far Left.”

I don’t believe these commenters are motivated by a nihilistic desire for destruction, and I treasure the fact that they feel comfortable disagreeing with me publicly.

Debate and discovery are what make a comments section good.

A fence and a last word

G.K. Chesterton’s parable of a fence is a useful heuristic for how I think of conservatism. The idea is that if you come across an old fence in an otherwise open field, and you want to tear it down, you need to stop and find out why it was put there in the first place.

If you discover the original reason is no longer sensible, then have at it. This investigatory pause will slow down change but it will prevent the destruction of things that are important, sacred, even existential.

Questions for the comments: Do you see yourself as a conservative as I’ve used the term? Or another political label you want to self-define? Anyone have a good word about nihilism? Favorite apocalyptical books or shows?

A day may come when ancient traditions fall prey to evil. But that day is not this day.

Relevant past essays include An Open Message To The Top 0.01% , a short history of my family’s generational wealth, and an interview of me by

about What It’s Like To Be (Very) Rich In New York CityIf there’s a true modern heir to Burke, I’m not aware.

Why do we only use the term GOAT––greatest of all time, but not WOAT––worst of all time? WOAT is now my version of “fetch” from Mean Girls.

In The Stand a bioweapon is released from a military installation by accident and kills almost everybody. The bad guys gather together in Las Vegas. The good guys gather together in Boulder, Colorado. Reading an apocalyptic book, you always imagine yourself as one of the .0001% survivors.

I always love your work David! When I was a union organizer for twenty years my more lefty friends would say, “Big labor is not revolutionary,” to me as a put down , but I would agree. My colleagues and I used to chant in a somewhat joking manner, “What do we want? Incremental change! When do we want it? Gradually!” We understood that people become psychologically unhinged when change is too fast. I see this in the poor urban children I teach. This year I am substituting again - have done both full time and subbed - and I try to maintain as much consistency as possible. The poor have very little structure and will embrace dysfunction if it’s routine. I worry about erosion or destruction of the social safety net because people will do irrational things if there is a disruption in their basic needs being fulfilled. Change is needed but not so fast it pulls the rug out.

Trump, Vance, Musk are all nihilists. They want to burn it all down... after they get theirs. The meme of 'leopards eating faces' is all over Twitter now, with teachers in the South, having voted for Trump, being surprised that their schools are at risk of losing Federal funding (it's the kids who suffer, of course). It's Musk trying to cuts costs, without damaging his own government contracts. It's Vance telling the EU to F themselves and Trump giving away bargaining chips to Putin for nothing in return. It's Apple and Google using Gulf of America.

The commenter who said sometimes you have to throw the baby out with the bathwater is a nihilist and I hope has no children.