When I was a young boy, most evenings we’d have a formal dinner, my sister and I with our parents. I’d sometimes stare up into the depths of the enormous crystal chandelier with its icy pendants.

My mother, keeper of etiquette, would ask me to redirect my attention to my much hated food. From the serving dish, the blameless maid gave me portions of that night’s meat and vegetable. I had to eat what was on my plate plus the salad in the crescent-shaped dish to my left.

My arch nemesis was beets. My heart would sink when I’d see them in the serving dish. I despised those red-purple discs that slid around in my mouth and tasted like something foul taken from the earth.

No bread and butter. No dessert.

In that era in our household, my two younger brothers, both in nursery school, ate in the breakfast room with their governess. They wanted to be at the big table, I wanted to be with them.

Challenging my father

My father was a big man with thick, dark hair and broad features. He came to the dinner table in his suit pants and dress shirt and delighted in talking about his day or explaining something to us.

My form of dinner-time rebellion was to lie in wait for my father to touch upon a topic that had any relevance, usually remote, to something I’d read or heard. Then I’d disagree with whatever my father had said.

For a boy in the fourth or fifth grade, I read a lot. But I’d guess that nine times out of ten I had no clue what I was talking about.

Sometimes my father would be amused by my precociousness because at the age of ten you can be precocious while making an irrelevant or incorrect statement. But there were times when he’d be irritated because even when I was contradicted by his adult, thirty-something knowledge, I’d hold fast to my position and refuse to admit I was wrong.

My refusal to ever admit I was wrong became a “thing” that my father wanted to reform in me.

At one dinner he became furious at me when I wouldn’t say the words “I was wrong.” He insisted. I resisted. Back and forth. Tears were gathering.

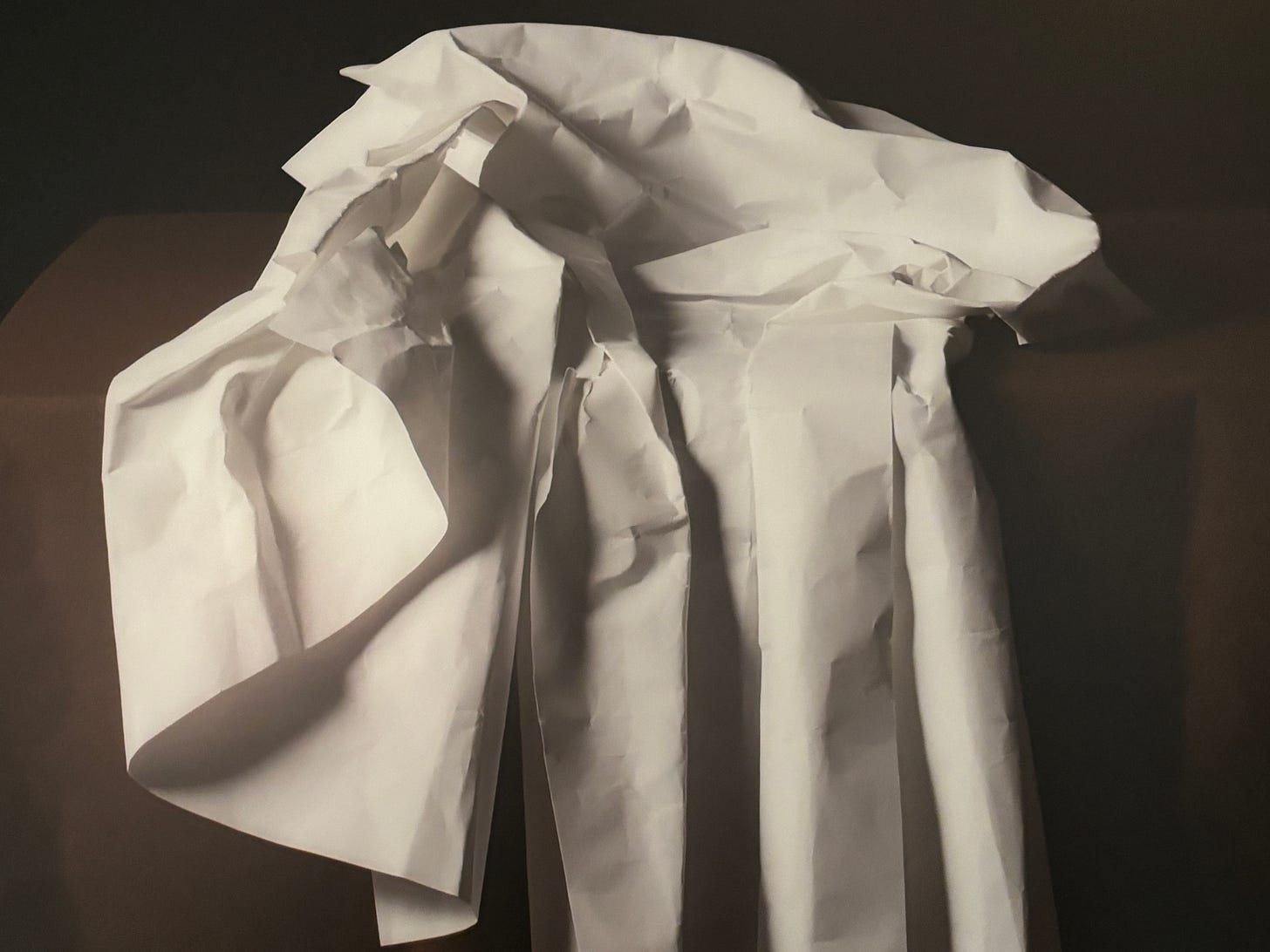

Finally he did or said something that made me rise from the table. I had crumpled up in one fisted hand the thick napkin embossed with my mother’s initials JAR.

In a final show of rage I threw the napkin down as hard as I could onto my plate.

Except my timing in releasing the napkin was off; I let it go too soon. So instead of flinging it downward, I sent it flying across the table at my father’s head. And it found its mark.

I ran down the long hallway to my room, but suddenly my father was there behind me. He spun me around by my shoulders and then used his long reach to whack my bottom with his hand.

The force of the blow was mild but the injury to my pride was catastrophic. I ran to my room. I remember being on my bed sobbing, face to the wall, with my mother there asking my father what had happened.

My father said he’d given me a potch1 because I’d thrown the napkin at him, an act he found inexcusable. But that hadn’t been my intention. The only words I could get out were “I didn’t.” My denial won no favors from my father since it appeared as if once again I was clinging to an indefensible position by refusing to admit my disrespect.

In my fantasy adjustment to this scene of my humiliation, my little brother Samuel, then four, but magically endowed with the sharp legal mind he has today at 56, toddles into my bedroom to tell my father that a crime requires not only the act but also the mens rea––the intent. Samuel declares me innocent.

This is a photograph created by a Dutch student meant to recall a painting of the Dutch Masters. More crumpled tablecloth than napkin but close enough.

My adult obsession

The young David back then, so afraid of being wrong, has remained part of me. But along the way my refusal to admit being wrong has changed to an obsession with being right.

There’s good and bad in that obsession.

Now, if I learn facts or points of view that correct my prior views, I must adjust my “settings.” Immediately. Because I consider a wrong fact or flawed point of view to be a dangerous parasite inside my brain.

I rid myself of wrong facts with a vehemence of self-criticism (Van Gogh was Dutch, not French, idiot!). It’s a potent mental weapon to turn on myself.

The worst is if I write something in error in one of my Substack essays. I can’t take it back. If only I had read the draft one more time, or done more research, or refrained from making the erroneous point altogether.

An error undermines the trust of my readers. Think about it. If you read anything in a book or an article you know to be false, perhaps because it’s on a topic you know a lot about, it’s natural to downgrade or even dismiss the rest of the writing. Or stop reading.

In speaking, however, I have recourse to the most intellectually conceited three words in the English language––“I don’t know.”

Conceited because of all the things I’ve said that evening––if at a dinner party for example–– I’ve only affixed the label of “I don’t know” to this one thing. I’ve implied that everything else I’ve said, you can take to the bank.

Judging judgment

The other issue with my obsession is that I get awfully judgmental to the point of anger when I encounter people who won’t admit they’re wrong. I’m not referring to opinions but to facts that are indisputable like numbers and transcripts of what people said or irrefutable evidence of what they did.

I’m good at spotting this judgment flaw in others because I’ve waged an internal war against the same defect in myself for my entire life. When I come across such a person, I will turn into my father at the dining room table and be relentless until I prove my point.

The judgment of who has the mental plasticity to change their mind and who does not is valuable and useful.

A medical judgment

My wife Debbie has a nerve disorder that a leading neurologist could not diagnose. He was an expert of long experience in certain mainstream methods of nerve disorder diagnosis. When his methods failed he could not fathom that anyone else could cure my wife.

He gave up.

After two years of frustration and a quantity of MRIs sufficient for Debbie to become friends with all the radiologists, Debbie found a new neurologist, Naomi. Debbie presented the history of her symptoms to Naomi, leaving out the prior doctor’s findings so that Naomi could approach Debbie’s case as a blank slate

Naomi listened carefully and patiently to Debbie; in fact she spent four hours listening to and examining Debbie on her initial visit. Naomi arrived at the correct, rare diagnosis, which she confirmed by a seldom used blood test. She prescribed the appropriate treatment, and now Debbie is recovering.

If I find that a doctor or anyone whose advice I might rely upon would cling stubbornly to a set of demonstrably wrong facts or refuse to consider other possibilities, whether it concerns their field of expertise or any other matter, I disqualify their judgment.

A mental superpower

However, when someone admits they’re wrong, especially about a deeply held and deeply felt conviction, my respect for that person’s judgment skyrockets.

Here’s a great example.

, a Substack political journalist was fiercely adamant that Biden should not be removed as the Democratic nominee. He published many Substack essays and notes to that effect. He was furious at those trying to get Biden to step asideAfter watching the Democratic convention, however, Earl published a post titled I Was Wrong. When someone can change their mind like that, it’s a mental superpower.

Mea culpa on “very fine people “

I’ll conclude with an error I made, which was pointed out to me by C.K. Steefel who writes Good Humor (which is indeed very funny and fun to read.) In a post from July, I made an ironic reference to Trump’s famous comment at a press conference saying that there were “very fine people on both sides” at the 2017 Charlottesville riot over the removal of a statue of Robert E. Lee.

C.K. pointed out to me that Trump’s words were taken out of context. It was false to allege that Trump had intended to label as “very fine people” the torch-carrying, White supremacist neo-Nazis who chanted “Jews will not replace us.” 2

I read the transcript. C. K. was right. 3

At that press conference Trump did condemn the White supremacists in unambiguous language. By “very fine people on both sides” he was trying to refer instead to the people who were allegedly peacefully protesting the removal of the Robert E. Lee statue.

But the actual video footage does not show any peaceful, pro-statue protesters. So while it’s clear from the transcript that Trump’s intent––his mens rea–– was not to call the White supremacists “very fine people,” by process of elimination he unwittingly did.4

In any case, my reference to that one muddled comment was lazy and unwise. There are so many other crystal clear comments before and after 2017 to support my own deeply felt views about this election.

Question for the comments: What do you do when someone you know refuses to admit they’e wrong about something that is irrefutable?

Potch is Yiddish for a light slap on the tush. It’s the only Yiddish word I can recall my father using.

They also chanted “You will not replace us.”

Here is the transcript of Trump’s press conference as reported by Politico.

Here is a Washington Post Fact Check article on Trump’s statement. It concludes from the evidence that Trump was wrong about the existence of peaceful “keep the statue” protesters.

David, what you didn't know, but what I'll reveal now, is that later that evening I met with mom and dad and pleaded you out to Involuntary Reckless Napkin Toss (Second Degree).

Good one, David, to see the longer and larger context of your early learning having brought you to where you are today. Many of us made course corrections that have served us better than if we had become entrenched and more stubborn in our refusal to consider the facts, the data, the research - all there for our benefit. My frustration is with those who either won't or can't open their minds to information that challenges their POV. It may be the teacher in me wanting to "correct" the mistakes of students or it may just be me still trying to help others become more enlightened. I have been wrong numerous times, made my share of mistakes and bad judgment and yet, here I am, not someone with all the answers, far from that, just an ordinary citizen who cares about what is good, beautiful and true. That goes for a lot of things, including the environment, the upcoming election and my own soul. Thanks for stirring the pot tnis Saturday morning.